Engaging with the concept of engagement

I am in the final drafting stages of a literature review on active learning spaces, one of the major projects I was committed to doing on sabbatical. A number of the studies my co-author and I included in the review approach the topic of “engagement” in some way or another. Although we see the need to discuss these results, I’ve been resistant to including that discussion in the paper because the term, “engagement”, is so poorly-defined that it seems meaningless. But it’s too popular of a concept to just leave out. So I drafted the following as part of the paper, and after the fact I thought it might make a good blog post. So here it is in first-draft form, formatted a little differently than it will be in the paper to make it more like a blog post.

One of the main questions in this literature review is: What effects do active learning classrooms (ALCs) have on student engagement? This dimension of the student learning experience is connected to, but quite distinct from the effects of ALCs on student learning outcomes such as exam and course grades or learning gains on concept inventories. A large number of the studies in this review targeted student engagement, and there has been a strong and sustained interest in “engaged learning” at all levels of discussion on teaching and learning, to say nothing of companies that manufacture furniture for ALCs1. The results of the studies in this review that specifically target “engagement” are therefore numerous, widely varied, and of potential use to many school leaders and educators.

However, we must first come to terms with the meaning of the word “engagement” as it relates to learning. Unfortunately, despite the wide usage of “engagement” in academic discourse, the term remains poorly operationalized. At times, it is defined in terms that describe certain student activities and behaviors, while at others it describes what parents, teachers, and school leaders do to elicit those activities and behaviors. Even when confined just to student-centered contexts, “engagement” can sometimes refer to the lived experiences of students in terms of feelings and emotions; at others, the behaviors of students that indicate a deeper level of involvement; at others, a set of beliefs or perceptions that students hold about their learning; while at others, it is a combination of these, often undifferentiated between the aforementioned aspects of “engagement”. There is no rigorous definition of “engagement” from which to conduct a scientific analysis of research on the subject, and given the wide array of meanings of this term in actual use, such a definition is unlikely to come to light in the near future.

We will not attempt to rectify the various concepts of “engagement” that permeate discussions of teaching and learning here. We will only give some background on the origins of the term, and then state a framework for “engagement” used to parse the various results in this review’s studies that pertain to engagement.

As Axelson and Flick point out in their article Defining Student Engagement, the term “engage” originally derives from a Norman word meaning “pledge”, so that to “engage” meant to enter into a binding obligation to another through oaths or laws. (The term “mortgage” derives from the same root and has a similar connotation.) The modern usage of the word is similar: To be “engaged” means to pledge oneself to a binding involvement with something or someone, much like the usage of this term in the context of a pledge to be married. In an academic setting, “engagement” can therefore be understood as a state of committed involvement in an activity into which we have entered willingly and with the intention to complete, and in which “we are entirely present and not somewhere else” (p. 40).

The concept of involvement speaks to a more modern origin of the concept of academic engagement. Alexander Astin’s research on student involvement in the 1980’s, the most-cited (on Google Scholar) of which is this paper from 1984, is considered by many scholars to be the forerunner of the modern notion of “engagement”. In Astin’s view, involvement “refers to the investment of physical and psychological energy in various objects” (p. 519); occurs along a continuum with different students contributing different levels of investment in the same objects; and has both quantitative and qualitative aspects. Astin further ties the quantity of student learning and development as well as the effectiveness of educational policy to the quality and quantity of student involvement.

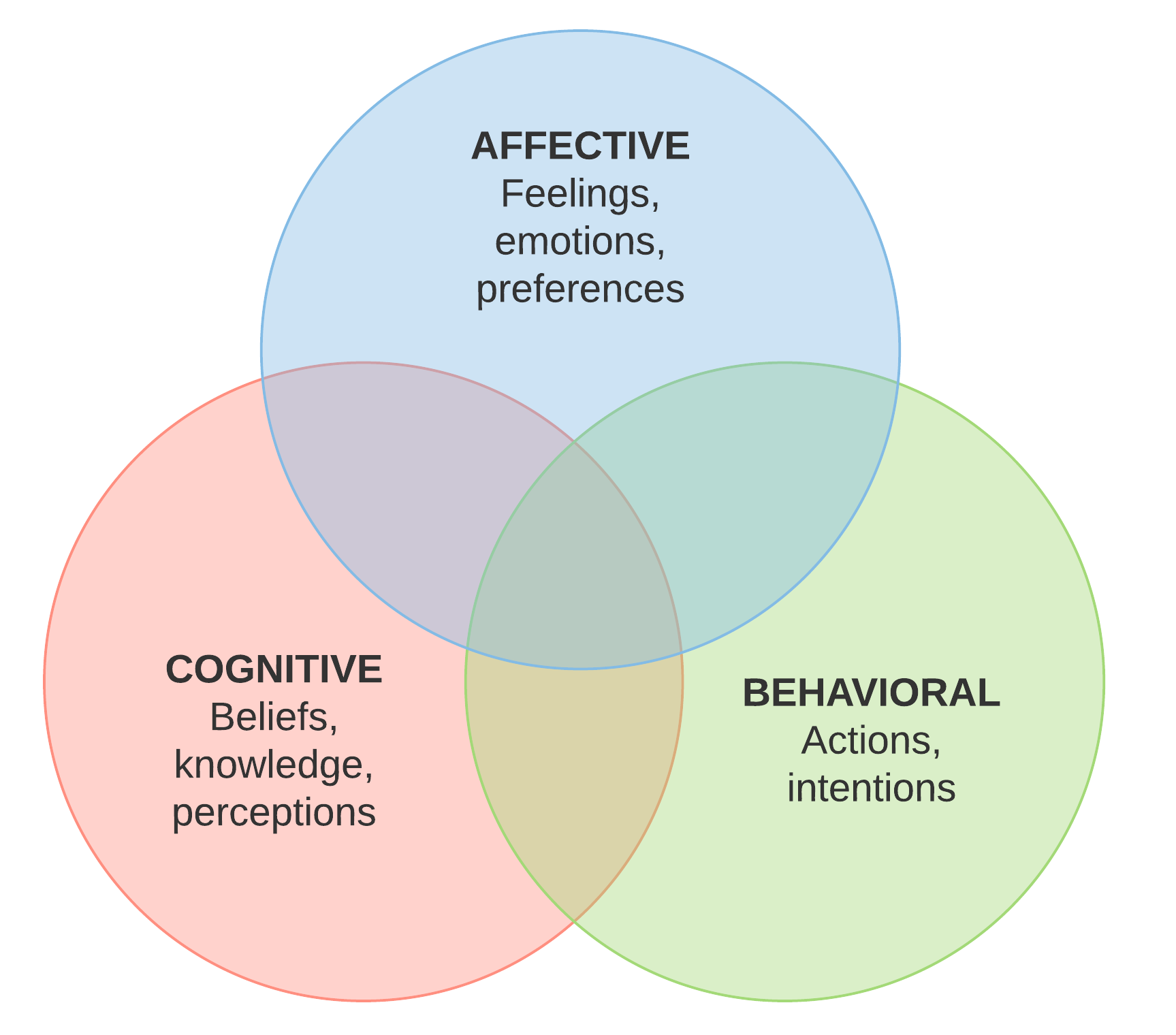

In later explorations of “engagement”, the qualitative and quantitative features of “involvement” tend to take on three distinct, yet strongly overlapping categories: affective forms of engagement, which pertain to feelings and emotions attached to student involvement (or the lack thereof); behavioral evidence of engagement, describing student actions that indicate involvement; and cognitive engagement, referring to beliefs, knowledge, and perceptions connected to involvement.

We note that this tripartite framework aligns well with the “ABC” (Affective/Behavioral/Cognitive) model of attitude promulgated by Eagly and Chaiken (for example, this book chapter) and others. Indeed, the modern concept of student engagement is closely tied to student attitudes about learning, and thus this framework for engagement is appropriate for the results found in this review.

Of the 46 studies identified for this review through our search, almost half of these — 22 in all — specifically target student engagement as the focus, or one of the foci, of their research. This is a remarkable proportion, but it seems completely in line with our experience with instructors, school leaders, and educational architecture and technology companies, a vast majority of whom indicate that improving student engagement is a primary goal. Further investigation, however, reveals that many of those studies targeting “engagement” have widely divergent ideas of what engagement looks like in practice. Some studies take a highly focused approach (for example, a study that observationally measures increases in student collaboration during class in an ALC and compares it against observed collaboration in a traditional space) or an approach to “engagement” that mindfully respects the diversity of ways that this concept can be approached (such as Lennie Scott-Weber’s Active Learning Post-Occupancy Evaluation, which synthesizes “engagement” from examining twelve different parameters across the “ABC” spectrum). Others, though, allow for variations in meaning of the term “engagement” that seem untenable. For example, one study counts merely attending class to be a measure of engagement — which is undoubtedly true on a basic level, but not on any higher level; other studies measure engagement in terms of sophisticated self-regulatory behaviors that go well beyong merely showing up for class.

Therefore, readers should take care when applying these results to their own interests. The concept of engagement does have some grounding in well-defined ideas and etymology, but its modern usage is so scattered as to render generalization from research results less than fully trustworthy. It is our hope that a sharper definition of this concept will be a focus of future theoretical work.

Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/deanhochman/27882707399

This is an Easter Egg.

-

This last phrase is definitely not going in the paper. But it’s true. ↩

Leave a Comment