Four challenges for flipped learning for the next five years

Back in January, I spoke at the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative (ELI) conference in a lightning talk session on the future of higher education. I summarized that session here but didn’t go into a lot of depth on my talk, which was on the future of flipped learning specifically. This week I was interviewed for an Inside Higher Ed article on flipped learning certification standards, and that plus the comment section for that article — which was marginally better behaved than the average comment section — has spurred me to go a little deeper here about what I discussed at the ELI.

Here are the slides from the talk:

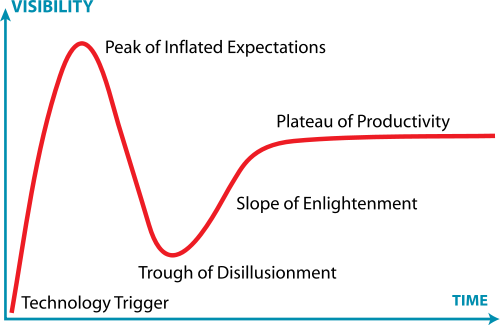

Flipped learning first started to emerge as an organized concept about 15 years ago, and both the research and practice really took off starting around 2010, with the rise of faculty development workshops on flipped learning that went viral and culminated in Jon Bergmann and Aaron Sams’ book. Published peer-reviewed research articles on flipped learning have been expanding at a rate of 65% per year, which works out to doubling every 18 months, since around 2013. Since most of that research consists of SoTL projects done in the field, in actual classroom situations, it’s reasonable to use the growth rate of research on flipped learning as a proxy for the growth rate of adoption of flipped learning in the classroom. So, this is a lot of research and a lot of adoption. I think it’s safe to say that flipped learning is not a flavor-of-the-month edu-buzzword1 that is breaking the hype cycle.

From my vantage point as someone who does a fair amount of research, writing, and reading about flipped learning, I think flipped learning is at a crossroads. We see explosive growth, but also it seems there’s a lack of a future direction with flipped learning. Flipped learning has come a long way in 15 years — but where is it going in the next ten years? Will it truly revolutionize the way teaching and learning are done, or will it finally fall off the hype cycle peak and settle into being a niche pedagogy practiced by a loyal but small number of instructors?

I obviously hope for the former, and to get us there, I propose four grand challenges for flipped learning for the next five years. I conceive of all four of these as building projects. Feel free to question just how “grand” these are, but if those who practice flipped learning can get behind them, I think good things will happen.

1. Build a standard operational definition of flipped learning.

One of the biggest challenges facing flipped learning is simply defining what it is. Several competing definitions, all with some overlap but also with nagging differences, are in use today, and this is making it all but impossible to conduct or interpret research on flipped learning or practice it with students. It’s to the point that if you hear an instructor say she uses “flipped learning”, you have to dig deeper to know what she really means.

So as the first challenge, and as a prerequisite to the others, I propose that somehow, we all come up with an operational definition of flipped learning that can serve as the standard for research and practice. I’ve already proposed my own. I’m not saying this should be the standard, but I think something like this could be the starting point. How will “we” decide on a standard, and who’s the “we”? I don’t know, but I think it will involve some group of people a high profile to lead the discussion and decide on one, and then start using it and labeling it as “the standard definition”.

Can other people use models of flipped learning, such as the in-class flipped model, that don’t conform to a standard definition? Sure. Who’s going to stop them? But we need a starting point.

2. Build a body of world-class educational research about flipped learning.

In a previous article, I noted that the growth in flipped learning research has been explosive, but the actual research has shortcomings and holes in it. There is a lot of research, but much of it has a distinctly garage-band feel to it, with lots of heart and enthusiasm but lacking in professional quality2. For the second challenge, I propose that over the next five years, we begin to fill in those holes and start to produce research with professional-grade quality and signature results.

I think the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences study from 2014 on active learning is a prime example of the kind of research I’d like to eventually see in flipped learning. This paper, a meta-analysis of over 200 studies on active learning, was done with the highest research standards, produced blockbuster results that settled the science about active learning, and was published in a premier scientific journal. Flipped learning doesn’t currently have a paper like this. We need one. Actually several would be nice.

While I think we still need to see flipped learning research along the lines that we currently do — on-the-ground reports from real teachers — we also need to aim higher. A good place to start would be the holes in the research that I mentioned in my earlier article: flipped learning and accessibility, flipped learning and students with learning disabilities, longitudinal studies, and meta-analyses of what’s already out there.

To get there, we need a way to take ordinary professors who are doing SoTL projects and either train them on educational research techniques, or pair them with professional education researchers (or both). As part of this challenge, I propose that we build a way to provide these training and partnership opportunities — perhaps in some way connected to challenge #4 below.

A back-of-the-napkin calculation says that well over 90% of all the research that has ever been done on flipped learning has been published in the last four years. Imagine what we can do in the next five.

3. Build a library of open educational resources for flipped learning for critical disciplines.

If flipped learning is such a great idea, how come not everybody is using it? By far the most common reason I have heard in writing and speaking about flipped learning, and talking to individual faculty members, is the time involved in converting a class over to this model — particularly the effort involved in preparing materials, usually thought of as making video. Even if you don’t use video in a flipped learning environment, there’s still no denying that it takes time to make the pre-class materials, prepare good in-class activities, and so on. That’s why I suggested a One Year Plan for newbies; but that doesn’t alleviate the effort, it only spreads it out.

To make it easier for all of us, old hands and newbies alike, to flip our courses, I propose that the flipped learning come together and create a repository of open-source, freely available materials that can be used for flipped learning, especially in the disciplines that seem to be most interested or needful of such things. Imagine a website or GitHub repo, full of videos, Guided Practice assignments or templates, in-class activities, online demos, formative assessments, and more that a person who wants to flip, say, an introductory biology class can simply go to and use, knowing that it’s been created and curated by other professors who are also teaching intro biology using flipped learning. It would reduce the overhead of getting started and sticking with flipped learning tremendously, and the #1 barrier to adoption would suddenly be gone.

I also propose, actually insist, that this be free, both as in beer and as in freedom. Textbook companies are beginning to bundle things like videos and online homework systems and advertising them as tools for flipping the class — as long as you pay for the book. I believe far more in an open platform for flipped learning that, like the research on flipped learning, is grassroots and infused with care.

I’m proud to say that at GVSU, we’ve made a start on this by producing two lengthy playlists of videos that cover the entirety of Calculus 1 and Calculus 2, that accompany my colleague Matt Boelkins’ Active Calculus book — and both the book and videos are free to use. The stuff is not perfect, but any calculus teacher (or self-teacher) who wants to use the materials can do so. Something like this, only much expanded, is what I would love to see. Our videos were made in two semesters and Matt’s book was written in one. Imagine what an army of flipped learning people can do in ten semesters.

4. Build a global network of local communities of flipped learning practice.

Finally, one thing that I’ve learned by going around and giving workshops on flipped learning, is that workshops on flipped learning are pretty worthless unless they don’t catalyze a community of users on that particular campus. If you bring in some outsider to talk about flipped learning, but there’s no corresponding community that persists after the outsider goes home, then the workshop may perturb the system in place but there will be no fundamental change in the system.

I’ve used “we” a few times here, as if there were a cohesive community of flipped learning researchers and practitioners out there. I don’t think there is. I propose we fix that. The way I see that happening, is on two levels.

- It first happens on local campuses and school buildings. When I give workshops, there are always a few faculty who show up and are surprised to see some of their colleagues there — “You do flipped learning? Me too!”. If you’re one of those faculty, make the effort to figure out who those other faculty are, and get their names and emails and form a local cadre of flipped learning people. Band together, get together for drinks or coffee once a month, and talk with each other about what you’re doing. Teach together, fail together, figure stuff out together. Leverage the people you work with and support each other. If you’re at a college with a center for teaching, they can help.

- Then, those vibrant local communities of practice can be connected across the globe through the internet and through conferences. There really are flipped learning people everywhere, and it’s amazing to connect on the same ideas about teaching and learning across campuses and cultures. Some of the most powerful experiences I’ve had in my career have been like this, for example last year when I connected with a large group of language instructors in Spain who are doing flipped learning in amazingly creative ways.

An active global network of vibrant local communities of practice is the slogan. By 2023 this network should be plain for everyone to see.

We have a really good start on this fourth and final challenge, actually. Groups like the Flipped Learning Global Initiative and flippedlearning.org exist for precisely this reason. There are also online groups like the Flipped Learning Slack team that connect researchers and practitioners in different parts of the world and different disciplines.

I’ve often said that soon, we won’t be talking about “the flipped classroom” — just “the classroom”, because flipped learning will be a normative practice and what is now traditional pedagogy will seem strange and antiquated. Taking on these four moon-shot challenges can give a lot of momentum in getting there.

Image: https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/small-bodies/asteroids/10199-chariklo/in-depth/

-

In fact I am pleased to see fewer and fewer instances of the word “buzz” in proximity to the term “flipped learning”. ↩

-

Because this sounds like an insult, let me recap what I mean: A fair amount of flipped learning research is done by educators who don’t have a lot of training in doing educational research, and so many of the published studies have issues in design choices, internal and external validity, and generalizability. Two other things to note: I’m completely self-taught on education research myself and so I count myself among these researchers; and second, I’d prefer to be in a research area that has a lot of activity and enthusiasm but has room to improve, than one that produces high-quality results but has no heart to it. ↩

Leave a Comment