Four lessons I’ve learned about giving talks

Somewhere along the way in my career, I started doing a lot of talks. It started with local math conference talks when I was in my previous jobs at small liberal arts colleges, because it was fun to talk about what I was doing in the classroom and these conference talks counted for scholarship in my tenure portfolio. Around the time I moved to GVSU, my speaking ramped up, with contributed talks at bigger conferences, then invited workshops for faculty at other universities, and eventually keynote addresses in the US and eventually abroad. These days, I go around and give invited presentations or workshops 5-6 times per year and it’s become something of a side job for me that I really enjoy.

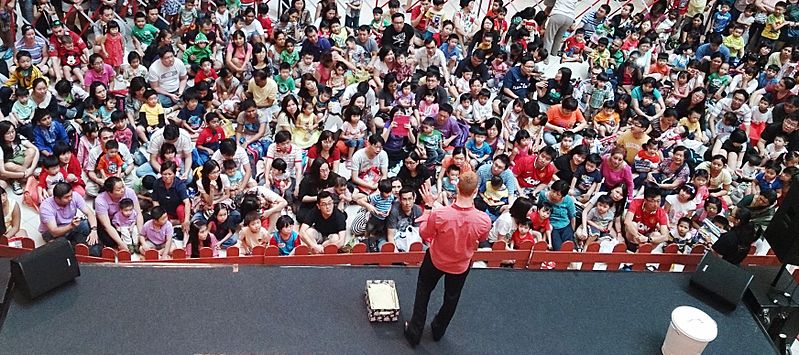

Recently I had the privilege to speak at TEDxGVSU. Giving a TED talk is a big deal. For many, it’s the pinnacle of what it means to be a speaker1. So, the experience of giving one gave me the opportunity to reflect on my development as a speaker. I took notes and wrote down a bunch of lessons that I have learned over the years, and I wanted to pass along the top of that list. I definitely have a lot to learn in speaking, but maybe some of these thoughts will be useful for you.

Please note that here I will merely affirm, rather than repeat, basic good advice about public speaking. Most of that has already been covered and done well, for example Tufte’s classic essay on PowerPoint, Joe Gallian’s How to Give a Good Talk (mainly targeted at math talks but applicable anywhere), or David Stern’s How to Give a Talk (presumably a good one).

1. Always assume that technology will fail.

Modern talks involve more tech than we realize. Most talks, at minimum, will involve a computer, a computer file that contains your slides, and a projector to project those slides. Probably there is a microphone involved as well, and therefore a PA system that the mics are connected to. Then there’s the second level of tech that includes things like the cables used to attach a computer to a projector, the internet connection in the room, and more. This is a lot of points of potential failure, so I live by the following:

The Law of Technology: Technology used for talks will fail in some way, either before or during the talk.

Sometimes all the tech used in a talk works perfectly. But, the Rule of Technology says that you must assume that any technology you use for a talk will fail at some point because the consequences for assuming failure are lower-stakes than the consequences of not assuming failure.

To live with the Law of Technology, I follow these three Rules of Technology:

- First Rule of Technology: Always have multiple contingency plans for tech failure.

- Second Rule of Technology: Always try as much as possible to force the technology to fail before the talk.

- Third Rule of Technology: When given a piece of technology to use in a talk, ask: Has this been tested to make sure it works with the equipment that I will be using?

For example, the First Rule would say that if you are using Google Slides, then

- Make the slides available offline on every device you have

- Also download PDF and PPT copies of the slides to your local storage

- Also download PDF and PPT copies of the slides to a USB stick apart from your computer

- If your talk allows, try to prepare so that you can use no slides whatsoever if things really go south.2

As for the Second and Third Rules, let me give a real-life example of what happens when you don’t follow them.

I was giving a talk in a semi-large auditorium, speaking from the stage but my slides were housed on a computer in the back of the room. I was to use a clicker to advance my slides, and I was handed that clicker a few minutes before going on stage. I got started with the talk and went to advance my first slide, and nothing happened. I clicked again, pointing the clicker up in the air, and nothing happened. I clicked four times in a row, pressing harder each time, and nothing happened. So, tamping down panic, I started into my talk for the next slide, improvising my words so that I didn’t need the slide. A sentence into this, suddenly the slides advanced 5 slides ahead, revealing an upcoming slide that I meant to build up to before showing it.

This went on through the whole talk, my actions with the clicker and the actual slide behavior seemingly uncorrelated. Later, the organizers determined that the distance from the stage to the computer in the back was so great that the signal from the clicker wasn’t being received reliably. It was a tech issue that didn’t get caught until it was too late. After the talk, the sort of comments I got were “Nice job, you really worked through that technology difficulty well.” That is, the talk was a failure: People didn’t remember my ideas, only that the damned clicker didn’t work.

Part of the blame for this is on me, for not following the Second and Third Rules:

- I should have insisted on a rehearsal of the talk that fully simulated the environment I’d be speaking in: Advancing my slides on that computer with that clicker on that stage in real time. This would have forced the tech issue to the surface before the talk, not during.

- When the organizer handed me the clicker, I should have asked: Has this been tested to make sure it works with the equipment that I will be using? If the answer was “no”, I should have insisted on a quick check or else an alternative. An answer of “It should be fine” is a “no”.

Technology is wonderful for giving talks, but it’s also one of the primary reason talks fail. So don’t trust it.

2. Always stick to the time limit.

Another of the primary reason talks fail, is that the speaker feels like the time limit on a talk is a suggestion, and it’s OK to blow past if if they get carried away. This is a clear violation of another law of mine:

The Law of the Time Limit: For every minute you exceed the assigned time limit for your talk, the audience’s understanding of your ideas and their esteem for you personally, are cut in half.

I don’t have data to prove this, only anecdotes, but they are strong anecdotes. I’ve sat in paper sessions that are an hour long and packed with six talks of 8 minutes each, and the first one reaches that 8-minute mark with the speaker showing no signs of wrapping up. A feeling of dread surges forward, like you’re watching a train speed toward an inevitable wreck. Could they not have practiced this, to make sure it’s coming in under the time limit? I ask myself. I am also thinking other thoughts that can’t be repeated in polite company. I will not remember what that person talked about, only that they went over time and messed up the whole session.

As an aid to following the Law of the Time Limit, I have this rule:

The 80% Rule: When preparing a talk with a time limit, replace the assigned limit with 0.8 times that limit and prepare the talk to fit within the new, shorter limit.

So if I were giving a talk in that session with 8-minute time limits, I’d prepare the talk to be about 6.5 minutes long. If it’s a 50-minute time slot (like a colloquium or job talk), plan and prepare for 40 minutes. And so on. This gives you breathing room in case of tech screwups (guaranteed by the Law of Technology), unsolicited audience questions, bizarre vocal tics, brain farts, etc.

Seriously, don’t ever, ever go over time. Conversely, finishing early has a 100% chance of success in getting your audience to think more positively about you.

3. Preparation is everything.

There is the temptation to put a talk together on the plane ride out to where you are giving it, or perhaps the night before in the hotel room, and then just sort of wing it. The top 1% of speakers in the world can pull this off consistently. The rest of us end up sounding like idiots.

How I prepare to give a talk depends somewhat on the talk itself, but generally I do the following in order:

- Figure out the main message and the overall story. What is the primary message you want the audience to remember? How will you build and support a story for this message that will make it memorable? For example, for my TED talk the main message was We can reshape math education so that computers are used to do things that computers are good at doing, so humans can do things that humans are good at doing. This should be no more than a couple of sentences, and should be so simple and succinct that you have no trouble reciting it from memory — because you want your audience to leave with this message as well.

- Visually outline the talk itself. Talks are usually visual, so before writing words or slides, use a piece of paper or a whiteboard to draw it. Screenwriters do this by storyboarding. You’ll remember your visuals better than the words you want to say; same with the audience. Those visuals will become your slides at some point.

- Write a script, time it out, and edit. Not that I follow the script; see below. But after the message and story are clear and the flow of the talk established, sit down with a text editor and just bang out what you think you’d like to say. Edit when done if you want. Then, read the script word for word while timing it with a stopwatch. If a straight read-through of the script goes over the 80%-Rule-adjusted time limit, then it’s too long, and you need to cut things out until it fits.

- Put away the script and practice with just the slides. Once the talk is the right length, draft out the slides using the visuals and begin to practice, using the slides but no script. My friend Lorena Barba, who is a rock star mathematician and a gifted public speaker, once told me that she doesn’t use a script — she said, I have a story for the talk, and I try to stick to the story rather than the script. I.e. if you have a strong message and clear story, all you need is to be occasionally reminded what to say next.

- Continue practicing in a faithful simulation of the talk environment until it’s consistently good and under time. I practice — standing up, speaking in a regular voice to simulate the talk, and with a timer — until I am comfortable enough that I can consistently give the talk under the time limit (remember the 80% Rule) and without needing my slides. If I can do that three times in a row, I feel like I am really ready.

I’ll admit, I don’t always follow this advice myself, but whenever I do, I have zero nervousness when giving the talk. I just go out and do it like I practiced.

4. Preparation isn’t everything.

(I love contradictions. Don’t you?)

As important as preparation is — and as religiously as I follow patterns of preparation — when I give a talk, I want it to be a spontaneous, human experience. I think people don’t so much want to hear the words of a talk but rather the interaction between the words and the person speaking them. It’s the ideas that ultimately matter, and that’s more than just words. Absent the personality and authenticity of the speaker, the ideas in a talk are just spoken text.

So the ultimate purpose of all the preparation I’ve mentioned to build a structure within which I can the freedom to talk to my audience from the heart, with side notes and a few rabbit trails, without losing the plot or getting off track. I don’t have a pithy Law or Rule for this, only that an important lesson I’ve learned is that when I give a talk, I am serving as the user interface between my audience and the ideas I am trying to get across, and as important as polish and preparation are, it’s equally important to be clear, authentic, and real. That’s a lot harder than just speaking.

Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Public_speaking.jpg

-

Although, I am skeptical in general about TED talks. ↩

-

Back in the day, I even used to make acetate transparencies of my slides just in case I needed to go analog. ↩

Leave a Comment