What being Full Professor means to me

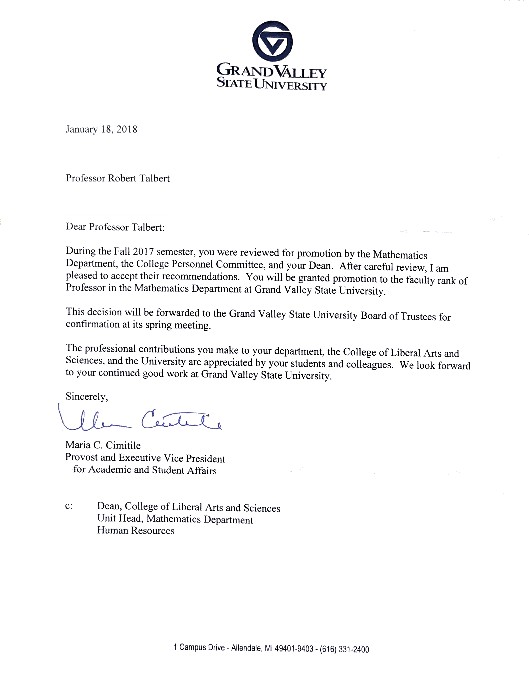

So a couple of weeks ago, this happened:

You might be wondering: Didn’t you just get tenure? Yes, back in May. When I came to GVSU in 2011, I had spent 14 years in other positions, so I negotiated for credit toward advancement. I ended up starting with no credit for tenure but at the rank of Associate Professor instead of Assistant. So the deal was that I would be up for tenure and promotion to Full Professor at the same time, in 2017. Due to an unforeseen quirk of our system, I ended up having to apply for tenure in one semester and promotion in the next semester rather than simultaneously. This meant two separate portfolios in consecutive semesters, which I don’t recommend. But I cannot complain about the result.

This is clearly a major milestone in my life and career, which began 20 years ago. I’m humbled, grateful, and keenly aware that nobody gets to this point in higher education without leaning heavily on the help, mentorship, and sometimes the mercy of other people.

You also don’t get to this point without thinking a lot about what’s ahead. I’ve had the good fortune of a year-long sabbatical, bookended by summers quite deliberately focused on nothing but rest and reflection — 15 months in all — to get outside my usual context and think deeply about where I am headed next and what this new senior rank (because although I’ve been tenured before, I’ve never been at Full Professor) means for me.

At its most superficial, being a tenured full professor means that I can basically do whatever I want in my job. I will never again submit a portfolio for consideration for continued employment or advancement1. So, if I wanted to shift my emphasis from teaching to research, I could do it. If I wanted to stop doing research altogether and do only teaching, I could do that too. If I wanted to retreat from professional work completely and just do the bare minimum required not to be fired, I could do that. It’s actually a little intoxicating.

And yet, just because I can do something, doesn’t mean that I should. I have no interest in, or plans for, doing the bare minimum, nor am I throwing caution to the wind in my teaching because I am now student-evaluation-proof. I will, in fact, do whatever I want; but “what I want” has evolved, shaped by 20 years of work with students and faculty. What I want, is to make higher education a place that truly lives up to its potential to be a positive force in the lives of students and to make the world a better place.

The work that all faculty do to this end is usually broken down into three areas: teaching, scholarship, and service. When we go up for tenure and promotion, we submit portfolios of evidence that we have met professional standards of excellence in all three phases of the game. The fact that I’m a tenured full professor won’t change that pursuit of excellence in each of those three areas. They are essential components of the profession and are mutually supportive.

But, here’s the new thing. Being a full professor means that there’s a fourth element added to this trio of teaching, scholarship, and service — a fourth area of responsibility that also demands excellence and also supports and is supported by the other three. That fourth area is leadership.

By leadership I do not necessarily mean “positions of authority” like department chair or dean. We all have many examples of people in positions of authority who don’t or can’t lead. What I mean instead is a combination of influence and initative used to inspire and drive others toward a common goal. Sometimes people in leadership positions are actually leaders. Sometimes people not in such positions are also leaders. But it’s still leadership.

Leadership is different from service as it’s used in promotion and tenure conversations. A person can demonstrate excellent levels of service in academia without being a leader, and that’s OK. Indeed, new faculty are expected to contribute to service but not expected to lead. In other words, junior faculty are expected to “do service” but are not expected to “do leadership”. After tenure, it changes: tenured faculty are expected to “do leadership” (often by being thrust into leadership positions) and “service” is no longer something you do but more like something you are — not a person who does discrete acts of service but someone for whom service is a continuous part of the job.

In my view, a similar transition happens when you go from tenured-but-not-full-professor to full professor, except with leadership. Being a full professor means not doing more discrete acts of leadership, but being a leader — someone for whom every professional act of teaching, scholarship, and service is either an act of leadership or an instance of failure of leadership.

This is a tall order, which is maybe why so few people ever go on to become full professors. And of course not all full professors are leaders — some shrink back into using their latitude and status to do the bare minimum. And I am not touching on the serious problem of proliferation of contigent faculty who do not usually even have rank at all, and are asked to work in a system in which they will never have real ownership, much less leadership. That’s a separate and critical issue. But as for me — having made it to this point through a combination of hard work, unearned privilege, and irrational persistence — I accept the challenge.

What does this look like, specifically, for me? Here are some thoughts.

One of the primary ways full professorship and therefore leadership works itself out, for me, is stepping up to be an advocate for junior faculty and non-tenure track faculty who don’t have the same voice or protections as I do. I have an obligation now to look out for the interests of these colleagues, to promote their development, to listen to their concerns, and to protect them from the dark sides of the system in which they are employed. I’ve exercised a similar responsibility for my students for 20 years. Now I get to extend that to my colleagues.

A related manifestation of leadership is to work to create the culture in higher education that I want to see. For me, that culture means learning is valued at all levels, not just with students but also faculty — working to build a culture that provides faculty with a safe space to explore, fail, and find their voice. Again, I’ve already been doing this with students; now I get to do it on a different level with faculty. I’ve learned a lot about the power of workplace culture at Steelcase this year; Steelcase is a company that values big ideas, values people, and values the development of ideas and people, and it shows in the way they do business. The leadership team at Steelcase is the primary mover behind that culture. The leaders in the company have a strong sense of the “why” behind their work and a genuine concern for the well-being of people. Higher education ought to have a similar culture but sadly often does not, getting mired in petty politics and selfish posturing. As a full professor I have an obligation to create the right kind of culture in my organization. (Which means that I also have an obligation to have a clear sense of purpose and a strong valuation of people, because the culture doesn’t happen without those.)

It also means that I have an obligation to infuse my teaching, scholarship, and service with leadership. It’s no longer just about my use of specs grading, for example, but about how to lead others in using it. It’s not about my research in flipped learning but being a leader in the flipped learning research community. It’s not just about doing the work assigned to me on a campus committee, or even serving as the chair of that committee, but rather being a campus leader who can see the road ahead and can get people moving in the same direction along that road.

So, I see being a full professor as not the end of a long road but the beginning of a new direction in the work that I am doing. It’s an intimidating responsibility but also a challenge that accept, and I hope that all of us who are fortunate enough to end up with this rank accept gladly and lean on each other as we work it out.

-

We faculty are required each year to make a professional plan for the upcoming year with plans for teaching, scholarship, and service along with any particular focus we choose; then at the end of the year we write a report on how well we did in meeting the goals of our plan. That report is used for annual merit reviews which impact salary increases. So there is some accountability but it is not make-or-break for one’s career. ↩

Leave a Comment