Grading with GTD

I can’t think of any aspect of academic work more problematic than grading. It can be difficult, time-consuming, tedious work without any clear reward for the faculty member. Grading itself is vitally important for students, because they need our feedback in order to grow in their mastery of our subjects. But for faculty members, grading can creep into every area of our lives, consuming time on weekends, time needed for sleep at night, and time needed to do all the other parts of our jobs that are also important.

As my sabbatical draws to a close, I am thinking about grading again, and a few folks have asked how the principles of Getting Things Done (GTD), which I detailed in my 10-part GTD for Academics series, specifically apply to grading. I’m happy to share my own experiences and solicit others’, because in 10 years of using GTD I’ve found that it has really kept grading under control. Using the ideas I’ll detail below, I still have a lot to grade, but:

- I only grade on weekdays, almost never at night or on the weekends;

- The average time I spend grading each weekday is about an hour;

- I am usually able to get student work back within one week; and

- I never get feedback from students saying I take too long to grade, in fact my evaluations usually mention how fast I return their work.

For context, I teach a 3-3 load with 30 students per class. But I think what I’ll describe below can help any faculty member including those with heavier loads or more research responsibilities.

One thing to note: Some of this has to do not only with using sound productivity principles but also good grading practices. My switch from standard grading to specifications grading plays a huge role in having a more positive experience with grading these days. Read more about that at the link.

So if this sounds good, let’s dive in.

Quick Recap of GTD

There are four habits at the heart of GTD: Capturing, Processing, Planning, and Doing. If you’re unfamiliar with these, read the articles at the links first. These four habits work together as follows:

- When something comes across our radar screens we capture it and get it out of our brains and into an external holding tank (physical inbox, notebook, note-taking app, etc.).

- Then we regularly go through each item we have captured and process it, deciding what it is and what to do with it. According to the GTD flowchart we can either trash it, defer it, file it away as reference, or act on it. Importantly, if an item is actionable and it takes less than 2 minutes, we do it right then; otherwise we determine whether it’s a single action or a project consisting of several actions, and decide What’s the next action I can possibly perform for this item?

- With all our items duly captured, we then regularly plan for when, where, and how we are going to act on the actionable stuff.

- Then we do — we get things done, by evaluating our time, energy, and context to determine the best next action out of all the next actions we could possibly do, and then executing.

Let’s see how the four core parts of the process work with grading.

Capturing

So let’s suppose you have some grading come in, either in paper or electronic form. Since grading is intentionally pushed to you, unlike a passing thought, capturing the actual work to grade is not an issue. However, the Capture process would say that the graded work has to go in a specific place until it’s processed.

- Paper grading should go in a physical inbox. Don’t just leave stuff sitting around on your desk, the floor, etc. For example I have a physical in-tray on my desk where anything analog that I have captured goes, including paper grading (although I mostly have students turn in work electronically these days) This sounds like an obvious thing to say, but have you ever lost a student’s paper before you can grade it because you got it mixed in with a bunch of crap on your desk that you forgot about, and then dumped it all in the recycle bin one day? I don’t recommend that.

- Electronic grading goes in an electronic inbox. If students turn in work by email, this is just your email inbox. If they turn it in on an LMS, then you’ll need to capture it your simple trusted system. For me, that’s ToDoist, and when something comes in to grade, I will enter it into my ToDoist inbox. Other systems, even just a paper notebook, work fine as well.

That’s the simple part.

Processing

Now that we have captured our grading, we have to decide what to do with it. Grading is definitely actionable; (sadly) we can’t trash it, delegate it1, or file it away. And also sadly, we usually cannot grade an entire class’ worth of work in 2 minutes or less.

According to GTD, we should then ask: Is the item I am processing a single action or is it multi-step? Here’s where the most important thing to remember about grading comes in:

Grading is always multi-step. That is: Grading items are never single tasks; they are projects that need to be broken down into small component actions.2

This was maybe the biggest revelation I had when first learning GTD, and it’s a huge shift in how many of us think about grading. Suppose you collect essay papers from 30 students, and you make a to-do list with “Grade essay” as one of the items. How likely is it that you’ll actually complete that “task”, or even think about it? This is not a task, and thinking of it as a task is a recipe for disengagement and procrastigrading. But when broken down into small pieces — “Grade Alice’s essay” for example — you can suddenly conceive of doing it, and in fact you can easily do it with a small chunk of time.

On small chunks of time: A main purpose of breaking projects into tasks, especially grading, is to harness all the small, under-15-minute chunks of time that float freely throughout our days. It may not seem like it, but most of us have a lot of those disconnected chunks. If we can reclaim those, and fit small tasks into a 10-minute block that’s otherwise going unused, then that’s 10 minutes more I have to spend with my kids in the evening and not grading. It adds up.

So, an item to grade is not a task, but a project. Here in the process step the question is how best to divide up the tasks that make up a grading project. Here’s the system I use. First, in your simple trusted system, enter in the graded item as a new Project. Then:

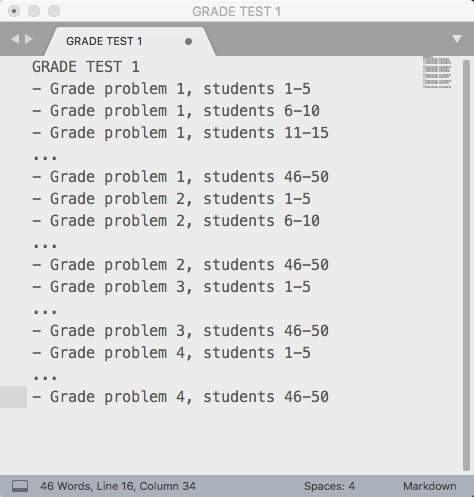

- Decide the criteria for splitting up the work. Your choices are usually: by student, or by item. For example, if you are grading essays and every student has turned in a single essay, it makes more sense to split the work up by student and grade one student at a time. If it’s a multiple-item test, it makes more sense to split the grading up by item — you grade everybody’s problem 1, then everybody’s problem 2, etc. — to keep the grading consistent. (You could also split up tests by page number; or by a combination of all these.)

- Decide how many things you can reasonably expect to grade in a single 15-minute time block. That 15-minute figure is arbitrary but the idea is to keep the time small so you can harness the disconnected chunks of time in your day. For example, maybe you can grade two students’ essays in 15 minutes; or a single problem on a test for five students in 15 minutes. The answer to that question varies widely, so use your judgment.

- Then, create one task in the grading project for each group of items you can grade in 15 minutes.

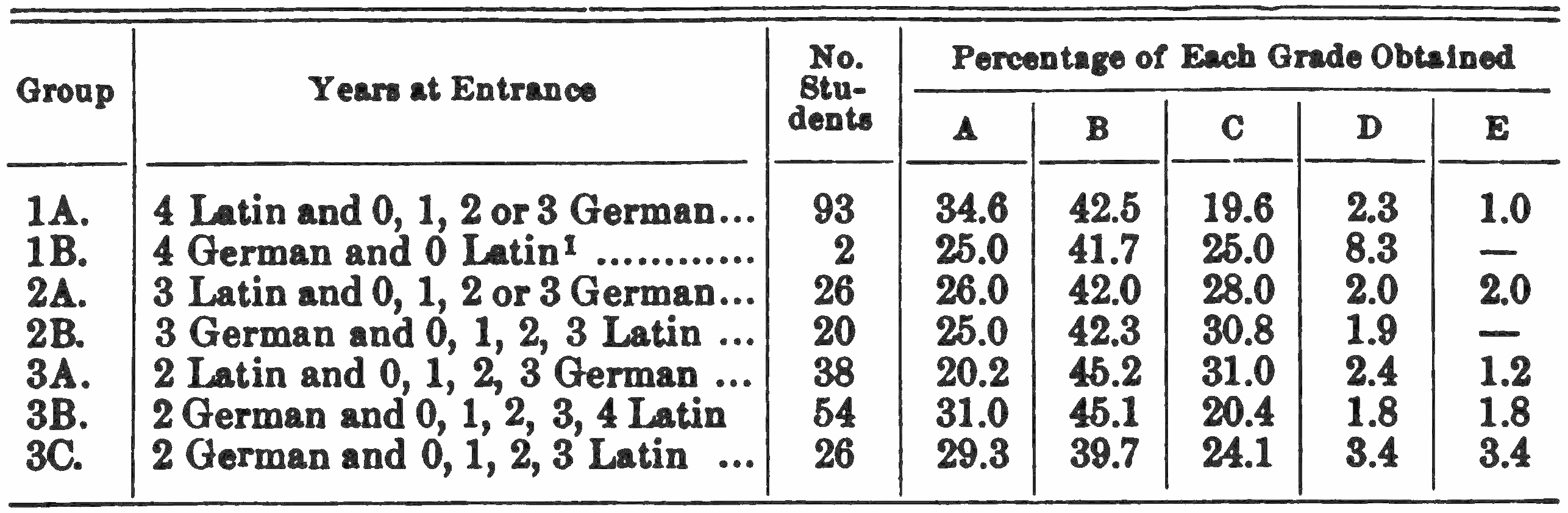

Example: In my Discrete Structures courses, students do “Challenge Problems” each of which is a single problem. So when students turn in Challenge Problem 4, for instance, I create the project Grade Challenge Problem 4 in ToDoist. Since each student is doing one problem, I split up the work by student. Based on my experience, I can usually grade four students’ work in 15 minutes. (The benefits of specs grading: I just have to decide if their work meets the standards or not, rather than wasting time assigning points.) So each task in the project is to grade four students’ work. The task list might look like this:

So I have seven tasks to complete in this project, each taking about 15 minutes.

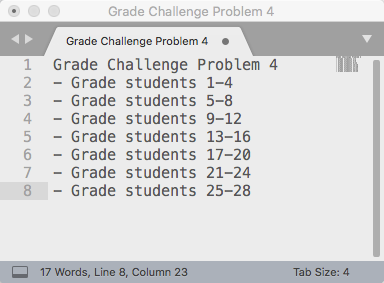

Example: Suppose you’re grading a test (call it “Test 1”) with four items on it and you have 50 students. In your system, create the project Grade Test 1. With a test, it makes sense to split the work up by test item. Suppose you also know that on average, you can usually grade one problem from one student in 3 minutes. That means each task in the project should be to grade one problem from five students (15 minutes’ worth of time). The task list would look like this:

I’ve put ellipses here to save space, but there are 40 tasks in this project: one task for each group of five students on one problem. That’s a lot, but this is a big project. If it really bugs you to have that many tasks in a project, split the project up into multiple projects — one for Problem 1, another for Problem 2, etc.

Planning

The point of splitting projects into small chunks is to give you the option to do one of those chunks in any small pocket of time that you may have. But we also have to build in time for grading rather than wait for those pockets to come to us. This has to be done intentionally. Taking weeks or even months to get grading back to students because you were “too busy” is not an option if you want to be good at this job.

My planning principles are:

- Start with a reasonable self-imposed time frame for completing the project. I’ve found that despite how it looks sometimes, students do not really want instant turnaround of graded work. What they want is a reasonably prompt turnaround time and a professor who consistently returns work within that time frame. The length of that time frame varies with the assignment, but for most assignments like homework, proof sets, etc. I tell students that they can expect to receive their work back within seven business days of my receiving it. This gives me over a week of real time to hack away at it3.

- Spread the tasks in the project out evenly over that time frame. This is simple math: Take the number of tasks in the project and divide by the length of your time frame, and this is the average pace you need to maintain for grading to complete the work in the time frame you set up. My Challenge Problem example, for instance, would say that I just need to complete one grading task per business day (7 tasks/7 days). The Test 1 example, if you used a 10-day window, would say four tasks — one problem from 20 students — each day. Doing this gives you a benchmark for how much you should be working on grading per day (more on this below).

- Build in dedicated time during the week for grading and put it on your calendar. When you do your weekly review, budget time for completing grading, especially grading items that rise to the level of “Big Rocks” for the week. You can create a single one-hour-per-day “grading time” if you want, or several times during the week where they fit, but the important thing is to schedule it and don’t move it. Grading is important and that other stuff will have its own time on your calendar.

As for when to schedule work, it should be times when you can engage in distraction-free work at a high energy level. For me, that time is 5:30-6:30am. I started this “Grading hour” practice when I was teaching a writing-intensive class a few years ago with a huge grading load. I started using this time — where the house is quiet, the kids aren’t up, and I have no distractions — to engage in deep work on grading. I did this to supplement other grading time during the week because of the high workload for this class, but later on I kept the practice up, and I find that one hour of deep work produces more results than 2+ hours when I am tired4 or distracted.

Doing

Once you’ve captured and processed your grading work and planned out the time to work on it, it’s time to actually do it. Pick a grading task to do — any next action in any of your grading projects — and work single-mindedly on that task, saying “no” to anything that isn’t that task. Shut down your email and social media (quit the programs, don’t just close the windows) and don’t schedule any appointments or allow drop-ins during your grading time. Get up and move somewhere else if you need to. Go dark.

But what if a student needs to meet with me? Don’t let them schedule appointments during your grading time, and if they are dropping in, tell them to come back later. Or better yet, get away from student contact altogether so you don’t have to “tell” them anything. But aren’t students the most important thing in our jobs? Yes, and that’s why you are going to be laser-focused on grading when it’s time to grade, so that you can have distraction-free non-grading time later in which you are fully present to your students. The same thing goes for colleagues who want to talk with you or that email that just popped into your inbox that I told you to shut off. We cannot be available to students 24/7 and expect to serve them well.

There are also non-scheduled grading times too. At any moment of your day, GTD says you should ask: What’s the next action that best fits the time, context, and energy I have available? Sometimes the answer is: A task from one of my grading projects. If that’s the case, get ahead of schedule by doing that task. It’s using those disconnected pockets of time to get things done.

Finally, maybe the most important suggestion here: Don’t spend more than your budgeted amount of time on grading in a single day unless you really want to. For example, if you have a grading project with 14 tasks in it and you’ve given yourself seven weekdays in which to get it done, then each weekday do two of those tasks — and then stop and move on to something else. Remember, all you have to do is stay on pace with those grading projects to complete them in the time you told students you’d get done. You do not have to get done any earlier than that. Do your budgeted grading amount per day and then stop and get on with the rest of your life. Seriously. The main reason for this GTD approach to grading is to put grading in a box so it doesn’t take over your life. This way, when you’re grading, you can feel good about grading when it’s time for that, and you can also feel good about not grading when it’s not time for that.

Grading is hard work and many of us have a lot of it to do. No productivity system is going to change that. But GTD, with its structured and disciplined approach to work that puts the human in charge of the work and not the other way around, can help us get a handle on it, and reclaim those nights and weekends for something better.

Let’s hear your suggestions and comments below.

-

Unless you have a grader working for you, which I highly recommend. ↩

-

There could be situations where grading involves a single action: For example if a single student is taking a makeup quiz and she is the only person doing so. I am describing here the typical case of a collection of items to grade for a whole class. ↩

-

I use “business days” because I intentionally try not to do any work on weekends. This is part of “fixed scheduling” as Cal Newport describes in his book. ↩

-

OK, I am pretty tired when I shamble downstairs with my black coffee at 5:30, but you’d be surprised how having coffee and something to do gets you going. ↩

Leave a Comment