How I wrote my book using Markdown, Pandoc, and a little help from the internet

Did I mention recently that I just wrote a book? I hope you’re not tiring of the self-promotion here and on my social media feeds, but I’m very happy with how the book turned out, and I want as many people as possible to get their hands on it. I had a great experience researching and writing this book. But when I started, I had no experience at all with the process of actually writing a book. I had to do a lot of research not only on things like cognitive psychology and pedagogical practices, I also had to figure the technical process of putting a book together.

With a project this complex, it turns out that you can’t just open up a word processor and start typing. There are issues to consider that don’t have a single right answer, and I had to figure out a way to deal with them that worked for me and my workflow. I got a lot of help from blog posts and articles about this as I was writing, so I wanted to share what I learned about all this in hopes that it helps others.

Fair warning: A lot of what I am about to describe can charitably be called “hacks”. There are probably simpler and better ways to do just about everything you will see. If you have an idea for improvement, leave it in the comments.

Markdown as the center of my writing universe

First of all, you have to understand how committed I am to using Markdown.

Markdown is a text processing platform that emphasizes making text readable while maintaining simplicity of form. If you’re new to Markdown, start here and then read anything you can about it, and try it out online or in a text editor. It would be a huge understatement to say that I am a fan of Markdown. Markdown for me is closer to being a lifestyle choice than a text processing system. I love Markdown: I love its simplicity, its portability, its lightweightness, its future-proof-ness. I write everything in Markdown unless there is a good reason not to: reports, syllabi, emails, even my blog posts and grocery lists.

By writing in Markdown, and keeping the content of my writing in what’s essentially plain text, I can open and edit it basically anywhere and on any device without worrying about compatibility. On my Mac, I write mostly in Atom, or sometimes in Sublime Text or Typora if I am wanting a change of pace. If I’m not around my Mac I can use Editorial on my iPad. If all I have is a web browser I can use StackEdit. The language itself is agnostic to hardware and operating system; it’s just plain text with a little spice added. Because it’s based on plain text, it’s uncomplicated, files stay small, and I know those files will be readable and editable 100 years from now.

At the very first stage of writing my book, I knew that I really, really wanted to write it in Markdown.

But…

My publisher, Stylus Publications, has been an absolute joy to work with. They have been supportive from the very beginning and are currently doing a great job marketing it. Everyone involved with Stylus, from my editor down to the person who arranges flyers for conferences, has been great.

But, Stylus doesn’t do Markdown. Stylus only works with Word documents.

It makes sense. I’m not a huge fan of Word, but one thing it does very well is track changes. Once I submitted the manuscript last August, it began a back-and-forth process where my main editor suggested large-scale changes; I made those and sent them back in; then there was a sequence of exchanges for copy editing where a large number of smaller detailed changes were proposed. By “large number”, I mean hundreds, ranging from typos to correct up to complete restructuring of paragraphs and sections. And not all of those proposed changes were ones that I wanted to make, at least in the way the editor suggested. So we had to have a way of proposing changes, accepting or rejecting or modifying them, and keeping track of them. Word is probably the best choice for that.

However, I didn’t relish the thought of writing a 300-page book in Word, to say the least. So I needed to devise a way to deliver a final product in Word, without actually writing it in Word.

Enter Pandoc

Fortunately I didn’t have to look very far. There’s already a great tool for doing what I wanted, and I had actually been using it for some time now: Pandoc.

Pandoc is a command-line program that basically changes any kind of (text-based) file into any other kind of (text-based) file. For example, you can use it to convert Word documents to HTML, LaTeX files to Word (with equations formatted!), plain text to ePub, and so on and so on. In particular, you can easily convert Markdown to Word. To convert foo.md to foo.docx, just navigate to the directory where foo.md is located and type

pandoc -s foo.md -o foo.docx

The -s stands for “source” and the -o stands for “output”. And that’s that — the Word-ified version of the Markdown file will just be sitting there in the same directory as the source.

So my plan became:

- Write each individual chapter as its own separate Markdown file. I wrote the book with the philosophy of keeping individual chapters short; this way it would be simple to compartmentalize all the individual pieces of the book.

- Combine all the Markdown files into one mega-file when done.

- Convert the mega Markdown file to Word with Pandoc.

There was one big obstacle to overcome if I was going to do it this way: Handling my references.

Managing references with BiBTeX

If you’ve ever written a journal article, you know that managing those references can be tricky. Each actual reference in the text has to be tagged with some kind of abbreviated information about it. Sometimes this is a number (for example, “[3]”) that points to a spot in a bibliography at the end where the full reference is given; sometimes it’s a list of the authors with publication date (for example, “(Lennon and McCartney, 1964)”). And there are different styles for citations like this.

Citing references in published work is at once extremely important — a core concept of scholarship being transparency in one’s sources — and unbelievably fragile. What if you write a 50-page paper that references an article 20 times, all with the label “[3]”, and then in the revision process you add or subtract a reference so that “[3]” is no longer the third reference in the bibliography? You don’t want to manually hunt down and change all the [3]’s; it’s mildly annoying in a 20-page paper and potentially insanity-producing in a 300-page book, and the possibility of missing one of those references is high. I didn’t actually count how many references my book has, but the references section is a solid eight pages long, including references to books, journal articles, websites, unpublished manuscripts, privately-conducted interviews, and more. So this was a big issue.

What you need is a way to automate references. For example, if that paper by Lennon and McCartney could be coded in as LennonMcCartney1964, and there were a system that allowed you to type in LennonMcCartney1964 whenever you referenced it and then automatically generate the bibliography at the end with the correct numbering, then keeping track of the [3]’s is no longer an issue. Fortunately, this system exists and has been used for decades, and it’s called BiBTeX.

BiBTeX is normally associated with documents written up using LaTeX, a markup language used for writing mathematical and technical documents. We mathematicians use LaTeX like we use oxygen; it’s the one technology that all mathematicians use. If I were writing a LaTeX document and I wanted to cite the Lennon and McCartney 1964 paper, I would just need to:

- Create a plain text file and enter in the citation info for the paper using BiBTeX’s format syntax. One piece of that syntax is a handle used for referring to the paper, for example

LennonMcCartney1964. - Go to the place where I want to cite the paper and type:

\cite{LennonMcCartney1964}. - Make sure the LaTeX source document has a few lines of code in it that tell it to process the BiBTeX file. And then,

- Just compile the LaTeX document. LaTeX takes care of auto-numbering the references and if these change in your text, the references will change when compiled again.

So BiBTeX is the right solution if you’re using a LaTeX document. Which I wasn’t. I’m a Markdown guy, remember?

Making BiBTeX work with Markdown and Pandoc

Fortunately, I stumbled across this blog post by seminary student Chris Krycho that gave me my final solution. It turns out that Pandoc can handle BiBTeX like a boss, even when the references are in Markdown files and not LaTeX files.

The way it works is like this.

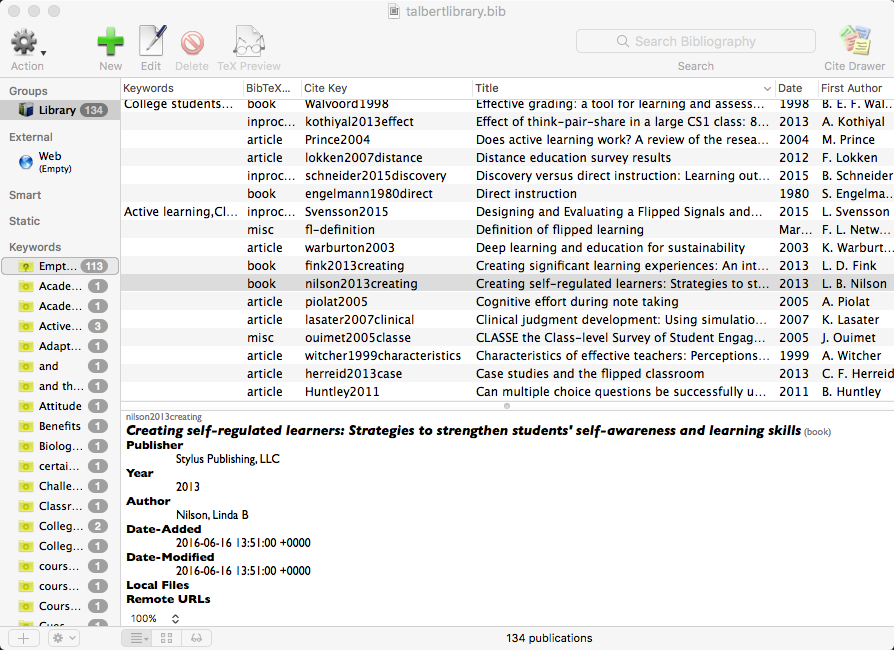

First, create a BiBTeX file for the references just as if you were using LaTeX. For the book, I used BibDesk, a free tool for managing BiBTeX files. But you could just use a text file for this. Here’s what BibDesk looks like with one of the references highlighted.

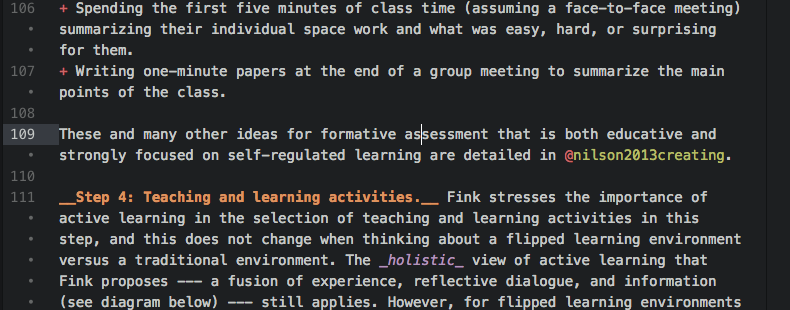

Then, in the Markdown file, whenever a reference is made, you just put the citation key for the reference prepended with an @ symbol. For example, the reference for the Linda Nilson book shown above has the citation key nilson2013creating. So when I want to cite it, I just type in @nilson2013creating like so:

This citation syntax is the Markdown analog of the LaTeX command \cite{nilson2013creating}. When the Markdown file is processed, that citation will turn into a formatted citation using a style that I can specify. How is this “processing” done, you ask? Using Pandoc. The command to get Pandoc to do all this is:

pandoc foo.md --smart --standalone --bibliography /.../talbertlibrary.bib -o foo.docx

where foo.md is the source Markdown file and /.../talbertlibrary.bib is the complete path to the location of the BiBTeX file that stores your references. (Mine was called talbertlibrary.bib.) The options being passed to Pandoc are:

--smart: This makes the typography look nice (converting dashes to em-dashes, etc.) and has nothing to do with the bibliography. But for the publisher, it matters.--standalone: The documentation says “Produce output with an appropriate header and footer”. Honestly I’m not sure what happens if you leave it out. I found it on the internet and didn’t want to mess with it.--bibliography: This is the parameter that tells Pandoc that you are pulling references from a bibliography. This is followed by the path to the BiBTeX file. The@syntax is rendered automatically.

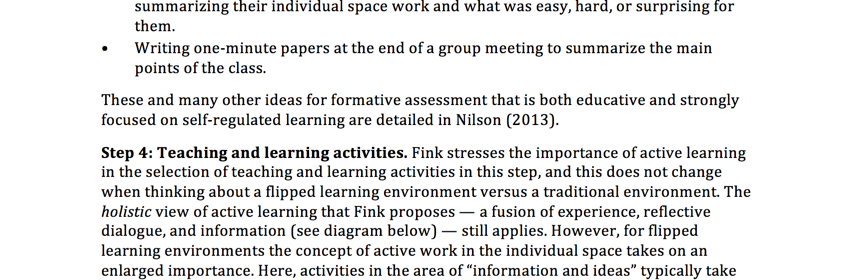

Again, once Pandoc is run, it produces a Word file. Here’s a screenshot from the results:

Very importantly: Pandoc also puts all the references at the end of the output file in an alphabetically ordered list. So you end up with a bibliography.

Finishing touches

Once I ran Pandoc on the mega Markdown file, I had a nicely formatted Word document with automatic references and a bibliography. All I needed to do to finish it was:

- Add a cover page, which the publisher wanted. Trivial to do in Word.

- Add a table of contents. This can be done in Markdown with Pandoc but it’s easier to do in Word, especially since the header syntax in Markdown that uses the

#symbol creates actual headers in Word, and Word’s table-of-contents generator uses headers to do its thing, which requires just a single menu selection. - On a couple of occasions, some of the images I had included with Markdown syntax didn’t look right after Pandoc. For example there were a couple of images that needed to go side-by-side, and there’s no way I know of to do this in Markdown. It was simpler to just add those after Pandoc.

And with that, I had a manuscript that was ready to go to the publisher, without doing any actual writing in Word.

Moving forward from there, everything was done in Word, again because that’s the standard file format that my publisher uses and it was important to track changes. But I’m OK with that, since none of the changes I made involved large amounts of actual writing.

Conclusion

Just as a postscript, my book doesn’t have a lot of math notation in it, but if it did, I could still use this workflow since Pandoc can render LaTeX expressions found in Markdown files, using MathJax. All you have to do is add --mathjax to the Pandoc command:

pandoc foo.md --mathjax --smart --standalone --bibliography /.../talbertlibrary.bib -o foo.docx

This produces a Word file with LaTeX-rendered equations in it. Or if you need the output to be a PDF, just change the .docx to .pdf; similarly if you want a plain LaTeX file, change it to .tex.

It’s always the case that you should use the best tools for the job. For writing my book, that tool was Markdown and a text editor for the writing portion; plus BibDesk for managing my references; and then Word for making it all look nice. I was really pleased to find ways to make all these interact, and I would strongly lean toward using this tool stack for any writing projects in the future.

Leave a Comment