Keeping it simple and getting things done: The move to a plaintext GTD system

As readers of this blog know, I’m a big proponent of Getting Things Done, the time/task/project/life management method detailed in David Allen’s book Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity. I’ve practiced GTD for almost 10 years and written a lot about it here on the website. One of the points I have made about GTD, especially for beginners, is the importance of not confusing GTD with the tools used to implement GTD. Many GTD newbies get caught up with GTD apps rather than GTD itself and fail to adopt the habits of mind needed to really succeed with GTD. The key is to develop the behaviors needed for good GTD practice first and then choose the simplest, most trusted system you can to implement it.

When I started using GTD, I used the venerable Kinkless GTD system that is just a collection of Applescripts that work with OmniOutliner files. Kinkless morphed into what’s now known as OmniFocus, and I was an alpha tester on the original, buggy-as-heck-but-super-promising OmniFocus releases. I used OmniFocus for 4-5 years before switching to Nozbe (I had traded in my iPhone for an Android phone and needed something non-iOS). For various reasons I got tired of Nozbe after a couple of years and switched to ToDoist, which has been my main platform for GTD…

…Until recently. I’ve switched again based on some new concerns I have had, not about ToDoist (which is IMO the best paid GTD app out there) but about the relationship that has existed between my GTD data — my “stuff” — and the apps that work with it. TL;DR – I have been experimenting with todo.txt, a minimalist GTD implementation that uses only plain text files, and it is pretty awesome.

The problem with tools

What got me thinking about my tools was the recent purchase of Wunderlist by Microsoft. Basically, Microsoft bought Wunderlist and promptly killed it, and reanimated its zombie corpse into something called Microsoft ToDo. This “new” tool sort of looks like Wunderlist and has a handful of the basic features of Wunderlist but none of the features that made it really useful for GTD.

While I wasn’t using Wunderlist when this happened, I felt the pain of all those Wunderlist users who were now scrambling to find a new tool to use and hoping that they can import their data into it successfully. This made me think: What if I had stuck with Wunderlist for my GTD system? How much time and energy would I be spending trying to maintain my system rather than actually getting things done? And who’s to say that what happened with Wunderlist won’t also happen with ToDoist or any other app that I use — being bought and killed off by a larger company, or being incompatible with the next macOS or iOS upgrade, or simply going out of business?

In some ways you can never get away from those concerns. I always have to trust the hardware and software that I choose. But I began to wonder: What tools for implementing GTD would give me the best balance of control, simplicity, and future-proof-ness — and decouple my data from apps? After doing some research and some thinking about this, I realized that the optimum solution was right under my nose: The humble plain text file.

The case for plain text

There are a lot of reasons to like plain text — including formats like Markdown and LaTeX that are based on plain text — for, really, anything:

- Text files are future-proof. They have been around since the beginning of computing and will be around long after all the apps we currently use are dead/gone/bought out by Microsoft.

- Text files are the ultimate in simplicity, containing precisely zero formatting and zero fluff.

- Text files are lightweight. You can have thousands of them on a storage device before they even make a dent, and sharing their contents is trivial.

- Text files are absolutely platform-independent, with high-quality text editors available on every OS and device1. They can also be turned into any other kind of format you want using simple tools like pandoc.

There is nothing inherent in GTD practice that says we can’t use something as simple as plain text files to handle our stuff. In fact in Leo Babauta’s book Zen To Done (which was the basis for my GTD for Academics series) he makes the point strongly that we have to keep the GTD system as simple as possible, and all that’s really needed are basic lists. That’s easily done with text files – or even just a notebook and a pen. The trick is in having a system for working with lists in text files to make it easy to search and filter stuff within the lists. It turns out there’s a simple, platform-agnostic system out there in use that works very well, and it’s called todo.txt.

todo.txt

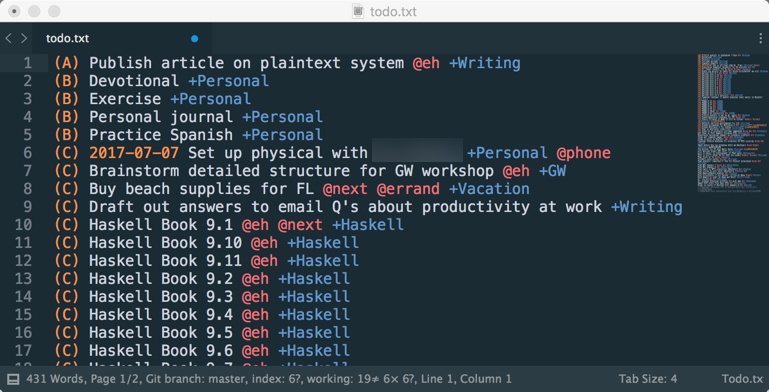

Todo.txt is a system of formatting plain text files for task and project management. It does not require any particular app and uses no proprietary file format. It’s merely a layer of syntax used in a plain text file for task management. Tasks are housed in a plain text file called todo.txt, one task per line and formatted using three different kinds of data:

- Priority, indicated using capital letters in parentheses,

(A)through(Z). - Context. These are indicated with an

@symbol, for example@phone. As in canonical GTD, context can refer to any sort of tag you wish to put on a task and is used for filtering tasks by physical location or tools available. I explained my use of contexts in this older post. - Projects, indicated with a

+sign, for example+BookReview.

Tasks can be labeled with any combination of priority, context, or project, including none of those. The system is flexible and you can use as many or as few of these data points as you want. In fact the only rules for formatting tasks are:

- Each task should appear on its own line.

- If a task has a priority, the priority is to be listed first.

- Contexts and projects may appear anywhere in the line but are to appear after the priority and start date.

- To mark a task as completed, put an

xwith a space at the beginning and put the date of completion directly following thex.

For example, here are correctly formatted tasks in todo.txt:

(A) Post blog article about todo.txt @computer +Blogging

(C) Call mom due:2017-07-15

2017-07-07 Read article about standards-based grading @online

x 2017-07-07 Draft article about todo.txt @computer +Blogging

The first task has a priority, context and project. The second has a priority and a due date but nothing else. The third has a start date and context but no priority or project. The last one is a completed task.

The other part of the todo.txt overall system is a second text file called done.txt that is used to house all your completed tasks. This is an optional piece of the overall system but most apps (see below) use it.

So, the whole system consists two plain text files, one holding the current uncompleted tasks and the other holding the completed ones, with simple syntax for managing the contents. That’s it. There are no apps, no proprietary formatting or rules, and no worries about portability or compatibility.

Really? No apps?

Well, there are actually plenty of apps for working with todo.txt. These are listed at the todo.txt main page and include a wide variety of approaches and platforms including natives apps for Mac, Windows, and Linux; Chrome extensions; mobile apps for iOS and Android; and more. All of these apps are merely graphical interfaces to the todo.txt file and none of them are necessary — you could just work with the plain text file in an editor of your choice if you wanted.

For me, the two most compelling “apps” for working with todo.txt for me are the todo.sh command line script and the SublimeTodoTxt plugin for the Sublime Text editor. The todo.sh script simply allows manipulation of the todo.txt file — adding and editing tasks, listing tasks filtered by search queries, marking tasks as done and archiving them to done.txt, and more — from command line entries. The SublimeTodoTxt plugin provides syntax highlighting, and I can bring the full power of Sublime Text’s features to bear on my tasks.

The header image on this post shows the top 1/3 of my current todo.txt file in Sublime Text so you can see what it looks like. It definitely satsifies that part of my brain — a large part — that craves simplicity.

My plaintext workflow (so far)

I started working with todo.txt a couple of months ago when my semester ended, because my workload this summer is low and so it’s a good time to experiment. I am still figuring some parts of my workflow out, but here’s what I have so far that’s worked pretty well.

I have the two essential files todo.txt and done.txt in a special Dropbox folder for syncing purposes2. I also introduced two other text files to help with my workflow: A file called inbox.txt for capturing incoming thoughts (I treat this as just another inbox, along with my email accounts, Google Keep, and my physical inboxes); and a file called masterlist.txt which contains a master list of all my projects and all the tasks associated with those projects.

My “stuff” goes through a progression of these four files — inbox, masterlist, todo, and done — as follows:

- Incoming “stuff” shows up gets captured into an inbox (not necessarily

inbox.txt). - On a regular basis — usually at my Weekly Review — I process all the stuff that’s accumulated in my inboxes. As discussed in this post on processing, items that are actionable and take more than 2 minutes and aren’t delegated to a calendar or another person end up in a task list —

masterlist.txtin this case. Tasks going intomasterlist.txtare given project/context/priorities and due dates if applicable. While todo.txt allows for up to 26 levels of priority ((A)through(Z)), I only use three:(A)designates most important things (MITs) for the day,(B)designates other stuff that are not MITs but which I would like to do today, and(C)designates stuff to do this week. Tasks that need my attention but don’t fall into any of those categories show up intodo.txtas tasks without priorities. - At the weekly review, I process through

masterlist.txtand if there are tasks that need my attention, I cut and paste them intotodo.txt. So all my tasks are split betweenmasterlist.txtandtodo.txt: The ones on my radar screen are intodoand the tasks that will eventually be on the radar screen, but not yet, remain inmasterlist. - On a daily basis, I have

todo.txtopen and make choices about what to do based on what’s in that file. Just as with any other GTD implementation, I make those choices based on my physical context, energy level, and time available. I have contexts set up to help me search and filter: They are the same contexts as I used in ToDoist, which I spelled out in this post.

The use of masterlist.txt in conjunction with todo.txt is my invention. In previous GTD implementations I would often find myself completely paralyzed trying to decide on a task to do, because I used my system to hold all the tasks I could possibly ever do on a project, and it would overflow my buffers with tasks that didn’t really need to be in my attention. I felt I needed to split the complete list of tasks into the ones needing attention and the ones that could wait. I did this in ToDoist with labels, but that wasn’t enough: I needed those tasks that didn’t belong on the radar screen to be out of sight and out of mind. For me, masterlist.txt is the staging area while todo.txt is where my attention is directed.

As far as apps go, I’ve tried out several and have gravitated toward these:

- On my phone (a Samsung Galaxy S8) I use the original Todo.txt Android app.

- On my iPad, it’s SwifTodo.

- On my Mac, I go back and forth between TodoTxtMac and using just the text file itself in Sublime Text and the

todo.shcommand line interface.

But note, none of these apps is necessary. I could easily just work with the text file in Sublime Text and many times I do just that.

Pros/cons

So far here’s what I like about todo.txt and what I don’t like as much.

I really love the minimalism of todo.txt. Working with plain text files is the ultimate in simplicity and control and portability. It gives me options for how I want to work with my data, and those data are not married to anybody’s app. Going with plain text does mean forgoing some features you’d get in a GTD app (see below) but what you get in return is a completely future-proof, fool-proof system.

I also love the fact that going plaintext makes me think a lot more about the nature of my projects and tasks and what role they play in the big picture. I spend a lot more time now thinking about why tasks appear in my system in the first place and whether they should have my attention or not. Before with ToDoist, there was so little friction in using the system that I could just forward any old email into my system without stopping to think about whether that email should go in the system. Now I think there’s an appropriate amount of friction there, and the things that end up in todo.txt truly belong there.

I’ve also been surprised at how little I notice the changes I’ve made. Aside from a few missing features that I’ve had to work around, I find that I am able to do everything I need to do without all the frills.

There are some things about todo.txt I’m not a fan of:

- There’s definitely not the vibrant community of developers you’ll find with ToDoist or OmniFocus. In fact there’s not much going on at all with todo.txt in terms of app development. Some of the apps mentioned on todotxt.com no longer exist, and some of Gina Trapani’s code for todo.txt on GitHub hasn’t seen a commit in 4-5 years. Using some of the todo.txt apps is like stepping back in time 6-7 years and I don’t mean that in a good way. SwifTodo, which is maintained by Michael Descy, is a big exception: He returns tweets minutes after sending and updates the app about once every six weeks, and the app – while quite basic – looks and behaves like a modern iOS app.

- Most of the todo.txt apps are based on syncing the

todo.txtfile via Dropbox, and this has led to some scary sync conflicts and data loss a few times for me. - Editing text files on a smartphone (at least on Android) has not yet evolved into a pleasant experience, and that’s your only option on mobile if you don’t want to deal with an app.

What’s next

I really like todo.txt and plan on continuing with it when I emerge from this summer and into my sabbatical, when I’ll have a real workload again and the system can really be put through its paces. In the meanwhile I am going to try to tweak and optimize my system. For example, while I have a reasonable rationale for using the masterlist.txt file, I’m not certain it’s necessary; and I am becoming fairly certain that I don’t need inbox.txt at all.

I also plan on doing some development of todo.txt tools, especially workflows for Editorial, my go-to text editor on iOS. Right now there is just one todo.txt workflow available (that marks tasks as done). I use my iPad more and more as my main computer for all but coding purposes and it would be nice to use Editorial as my todo.txt “app” (even though SwifTodo is a very good app by itself).

Finally, I’ll just note that my move to todo.txt is part of a larger push to move everything I do to plain text files, patterned after this Plaintext Productivity system outlined by SwifTodo’s Michael Descy. I’ll have more on that big picture in a later post.

-

Except Android apparently. If I’m wrong on that, give me your recommendations. ↩

-

You could argue that using Dropbox defeats the whole “decouple your data from apps” ethos here and there’s some truth to this. I suppose I could self-host the data, but (1) most of the apps for todo.txt use Dropbox for syncing, so if you use the apps you need to use Dropbox and (2) call me naive, but I trust Dropbox from having used it for almost a decade. ↩

Leave a Comment