The power of confronting what we don’t know

Last month I spoke at Indiana University about the research connected to flipped learning. As I was putting together a composite view of research findings on student attitudes and affective responses to flipped learning, I found something weird and frustrating, but sadly not very surprising: When students experience flipped learning, after a brief period of adjustment they tend to understand its benefits pretty well and can articulate those when given open-ended questions about their experiences. They agree that flipped learning provides increased connection with their classmates, deeper conceptual knowledge, and heightened access to and attention from their instructors. Their grades are usually better too. But that’s not the frustrating part. This is: Generally speaking students still want instructors to go back to traditional lecture and will express a desire to go back to traditional instructional methods in the same breath used to express the benefits of moving away from traditional methods to flipped learning.

What’s with this? One explanation is that students are just lazy and would rather have a learning environment that places low demands on them but yields fewer learning benefits, than a higher-demand learning environment with greater benefits. But I’m skeptical of appeals to laziness, as those appeals are often themselves good examples of lazy thinking. It could also be that students want it all: The ease of the lecture environment, with all the benefits of flipped learning. And a pony. But this is just another instance of laziness.

Something that Maryellen Weimer wrote recently seems like a better explanation. She was writing about how we may be missing the point on active learning, if we focus on active learning techniques but fail to provide students with an essential active learning experience:

I’ve been helping my colleague and good friend Larry with his book. In the chapter we’ve been working on, Larry writes, “Learning starts with things—things in all their details and ambiguities are the stuff of reality—they incite curiosity.” That’s another way of saying that techniques are secondary, maybe not even needed if we start with real (tangible or intangible) things. […] Larry recommends selecting things that confront students with their ignorance—so they see clearly what they don’t know, can’t understand, don’t see the reason for, or can’t make work. When you’ve got an artifact in front of you, there’s motivation to deal with it. Think for a moment of what happens when you give most any of those millennial students a new electronic device. Usually, without the instructions and no attention to technique, they start playing with it to see how it works. Do they mess up and make mistakes? Do they give up or worry about looking stupid? Does active learning in our courses look anything like this?

I think this idea of confronting ignorance is at the heart of many student reactions to active learning in general and flipped learning in particular. That idea is in many ways the entire idea of education in a nutshell, or at least it should be. One of the main purposes of education is to expose us to how much we don’t know, and help us add to our store of knowledge and equip us with the tools to continue that addition process throughout our lives. That starts, on a daily basis, with coming to terms with the fact that there is stuff we don’t know.

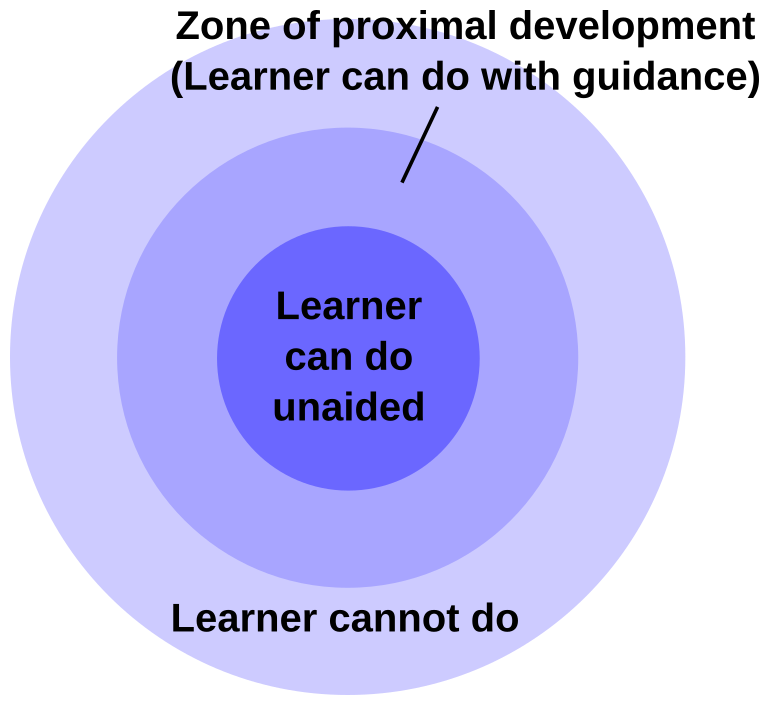

For an experienced learner, this confrontation with ignorance is like an old friend. We recognize that ignorance is not inherently a bad thing but rather simply part of the human condition, and confronting it is therefore a deeply humanizing act. It can even be fun because encountering that boundary zone between what we know and what we don’t know is an opportunity for growth and exploration. We have a chance to exercise our well-developed frameworks for learning and add to the store of what we know, even while at the same time that boundary zone expands.

But for inexperienced learners, which surely includes the vast majority of college students despite more than a decade of experience in school, being placed in this boundary condition where the confrontation with ignorance happens is part threat, part insult. College students, especially newer ones, tend to be in the lower Perry stages of development and remain within the safety in the knowledge they have. Being placed at the edge of that knowledge and made to move forward into the unknown is asking them to leave that safety. It can also be perceived as a way of saying, You’re stupid. Here’s proof.

If that much is true, then student responses to flipped learning and other active learning frameworks really make sense. Flipped learning is based on putting students in that boundary zone all the time: Before class by asking them to teach themselves the basics of new material (i.e. stuff they don’t already know, without the expectation that someone will do it for them), in class by having them jump straight into advanced work with the assumption of reasonable fluency on the stuff they were supposed to teach themselves (with no expectation of being bailed out by the instructor), and after class in even more advanced and longer-term projects. Every point of contact with the class involves being placed right at the front lines of the battle to learn, always aiming for the zone of proximal development, and we never let students get too comfortable with what they know.

This kind of learning environment puts a lot of pressure on students — appropriate pressure, I think, because to be a lifelong learner means being skilled in navigating this zone, and higher education should serve to get students to this point. But it’s easy to lose track of just how challenging flipped learning or even simple active learning instead of plain lecture can be, for students whose experience with learning is confined to taking lecture notes and then replicating them on a test. It also paints a sobering picture of what the instructor in flipped learning can look like for these students. Being made to confront ignorance on a regular basis can simply feel like the instructor is saying: You’re stupid, I enjoy telling you so, and I am not going to lift a finger to help you.

This confrontation between a person and what they don’t know, holds tremendous power. It can lead to powerful learning experiences and growth that last a lifetime, because it changes you. But it can also create powerful misconceptions in students about themselves. And we teachers are in a position to direct that power, or direct our learning environments away from it.

There are two responses that instructors can have to this realization.

We can appoint ourselves as protectors of students and deliberately shield them from the difficulty of encountering and dealing with ignorance. This can be done in several ways. We can retreat from active learning and simply lecture all the time1, thereby telling students that the job of confronting their ignorance is our task rather than theirs, like an overweening parent who rescues their kids from every difficulty the kids ever encounter, even if it hurts the kid’s development. We can give students work to do that remains in the “safe zone” of what they already know and never ventures out into the unknown. We can instruct students in such a way that they feel good and feel as if they are learning, without them ever actually learning anything, or without our ever assessing what they truly know and — especially — don’t know. If we go this route, and we have a sufficiently fun personality, the faculty-student nonaggression pact will be preserved, and our RateMyProfessors.com and course evaluations will glow.

Or, we can keep the above ideas in mind when we teach using flipped learning or something similar, and redouble our efforts to support and encourage students to embrace the challenge and help them through it. This doesn’t mean dumbing down our courses. It means, for example, keeping in mind the concepts of self-determination theory and cognitive load theory and making appropriate course design and instruction decisions that help students meet the high standards we set (for example, by reducing the extraneous cognitive load that our assignments may place on students). It also means we make it explicit to students that while the content we teach in our courses may or may not ever be used by those students, the processes of learning will be of constant help as they learn throughout their lives, and so we embrace the process and explicitly teach the process and not just the content.

I obviously prefer door #2, as it is truer to what higher education could be: A means of equipping students to grow themselves, apart from me, throughout their lifespans and confront ignorance with a happy determination that can make life more meaningful.

Images:

- https://pixabay.com/en/line-floor-leaves-red-boundary-2917062/

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zone_of_proximal_development.svg

-

Let me reiterate something I’ve said before: Lecture is not inherently bad. Lecture is a tool that every professor should have sharpened, and use it well in the instances where it’s called for. But: Using it as the only tool for every job, failing to give formative assessment to students in lecture to see if they are actually learning anything and failing to change course if the results come back unfavorably, or failing to get students in any way involved actively with the learning process, is simply an advanced form of helicopter parenting and is not only bad but unethical. ↩

Leave a Comment